Spinal Stenosis: Clinical Insights into Types, Causes, Symptoms, and Advanced Treatment Modalities

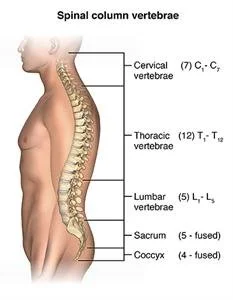

Spinal stenosis is defined as the pathological narrowing of the spinal canal, foramina, or lateral recesses, resulting in mechanical compression of neural structures. It is most commonly seen in the lumbar and cervical spine. The condition is categorized as congenital or acquired, with the acquired form typically caused by degenerative changes such as intervertebral disc herniation, facet joint hypertrophy, ligamentum flavum thickening, or spondylolisthesis.

The clinical course of spinal stenosis varies depending on the severity, level of compression, and patient-specific factors. Timely diagnosis and a personalized treatment plan are critical in preserving neurologic function and optimizing spinal mobility, especially in patients with progressive symptoms or functional impairment.

Types of Spinal Stenosis

1. Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

The most common type, associated with lower back pain, sciatica, and neurogenic claudication (pain and weakness in the legs while walking).

Frequently degenerative in nature, often occurring at L4-L5 and L5-S1 levels.

2. Cervical Spinal Stenosis

May present with neck pain, numbness in hands, gait instability, and in severe cases, cervical myelopathy.

Considered more urgent due to the risk of spinal cord compression.

3. Thoracic Spinal Stenosis

Rarer, but can cause significant mid-back pain and neurologic dysfunction when present.

Causes and Risk Factors

Spinal stenosis is typically multifactorial. Common etiologies include:

Degenerative Disc Disease: Leading to loss of disc height and canal narrowing.

Osteoarthritis of the Spine: Causes hypertrophic changes to joints and ligaments.

Herniated Disc: Protrusion of disc material compresses spinal nerves.

Spondylolisthesis: Forward slippage of vertebrae narrows the canal.

Congenital Narrow Canal: Present from birth, predisposing to early symptom onset.

Spinal Trauma or Post-Surgical Changes: Scarring or alignment changes after injury or surgery.

Risk factors include aging, genetic predisposition, poor posture, spinal injuries, and occupations involving repetitive bending or heavy lifting.

Symptoms of Spinal Stenosis

Symptoms are gradual in onset and often exacerbated by activity. Common clinical features include:

Localized back or neck pain

Radicular pain radiating to arms or legs

Tingling, numbness, or burning sensations in extremities

Muscle weakness or foot drop

Balance and gait disturbances (especially in cervical myelopathy)

Bladder or bowel dysfunction in severe cases (cauda equina syndrome – surgical emergency)

Diagnostic Evaluation

Accurate diagnosis involves a combination of clinical assessment and imaging modalities:

MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): Gold standard for visualizing soft tissues, neural compression, and disc degeneration.

CT Scan (with or without myelogram): Provides detailed bone anatomy in patients unable to undergo MRI.

X-ray: Useful for detecting alignment abnormalities and degenerative changes.

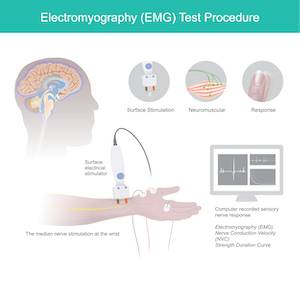

Electromyography (EMG): Assesses nerve root irritation or chronic denervation in limb muscles.

Treatment Options for Spinal Stenosis

The choice of treatment depends on symptom severity, duration, and response to conservative care.

1. Conservative Management

Physical Therapy: Focuses on core strengthening, spinal flexibility, and postural correction.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Reduce inflammation and alleviate pain.

Epidural Steroid Injections: Provide temporary relief in radiculopathy or neurogenic claudication.

Activity Modification and Weight Management: Crucial in delaying disease progression.

2. Interventional and Surgical Therapies

When conservative measures fail, or neurological symptoms worsen, surgery is indicated.

Laminectomy: Decompression by removing the lamina to relieve pressure on nerves.

Laminoplasty (for cervical stenosis): Expands the spinal canal while preserving motion.

Minimally Invasive Decompression: Uses smaller incisions with less muscle disruption and faster recovery.

Spinal Fusion: May be necessary in cases of instability (e.g., spondylolisthesis).

Interspinous Process Devices: Alternative for select lumbar stenosis patients not suitable for fusion.

Prognosis and Long-Term Outcomes

With appropriate management, patients can experience significant pain relief, improved mobility, and enhanced quality of life. Surgical intervention, particularly decompression with or without fusion, shows high success rates in well-selected candidates. Factors associated with favorable outcomes include early intervention, absence of significant comorbidities, and adherence to postoperative rehabilitation.

At MedTravel, we connect patients with leading board-certified spine specialists in Seattle who provide evidence-based evaluation and care for spinal stenosis. From non-surgical management to robotic-assisted spine procedures, we offer access to top-tier technologies and expert-guided treatment pathways.

Our team manages your care from pre-consultation through recovery—seamlessly coordinating with postoperative partners to ensure continuous support during rehabilitation and beyond. Whether you are a local patient or pursuing medical tourism for orthopedic care, MedTravel is your trusted partner in spinal health.